|

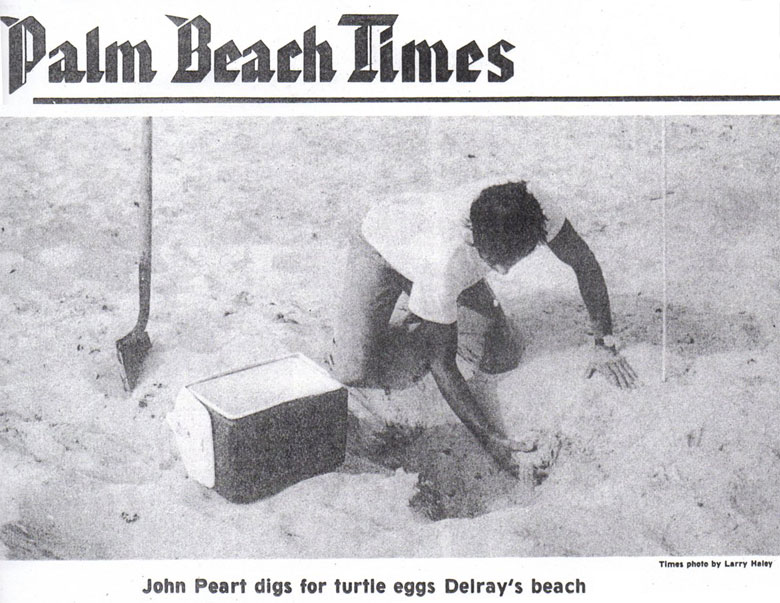

Salvaging baby sea turtles his job Sand dumping in Delray threatens nests of eggs By LARRY HALEY Times Staff Writer DELRAY BEACH — Armed with only a probe stick, a shovel and a bucket, John Peart stalks Delray's public beach at 6 a.m. Each day looking for baby sea turtles. No, he's not a poacher out to steal the eggs of the endangered sea turtle. He's the city's one-man fight against the extinction of the creatures that crawl out of the ocean during the summer months and deposit their eggs deep in the sandy beach. One month ago, Peart, an animal lover and owner of a beach maintenance company was hired by the city to midwife Delray's endangered sea turtle population. In the next couple of months, a beach re nourishment program will begin when 500,000 cubic yards of sand will be pumped onto the public beach to guard against erosion along the south county coastline. The turtles would soon perish under tons of sand unless the nests are relocated, Peart said. So far, Peart has relocated about 34 turtle nests — an estimated 4,000 eggs. He plans to move another 4,000 to 6,000 turtle eggs before the pumping program begins. The turtles are moved south several miles to the more remote beaches of Highland Beach where there is less artificial lighting to steer the baby turtles off course in their journey from the beach into the sea and less people to molest the nests. A major threat to the survival of the sea turtles along the South Florida coastline is a creation of man — the ordinary street lights along State Road A1A. Peart said the street lights destroy more baby sea turtles than perhaps all of its natural predators combined. When the young turtle hatches from its egg, it rises from the sand-covered nest and by thousands of years of instinct follows the early morning sun to the ocean. With the advent of development along the coastal areas and street lighting, the young turtles mistake the lights for the sun and head toward A1A rather than the ocean. The end result is either the small turtles are smashed under the wheels of passing vehicles or they wander around the sand dunes until the heat of the mid-day sun kills them. "The baby turtles cannot survive out of the water during the hot sun," Peart said. “They are fried before the first day out of the nest is over." Even without the treat of going in the wrong direction out of the nest, the first moments of life are perilous for the tiny creatures. Peart said that shortly after the turtles leave the nest, land crabs stalk them for food. If the creatures make it to the water's edge, other hazard lay ahead. For example, seagulls soar low across the shallows offshore keeping an eye out for a baby turtle swimming out to sea. Then there are more crabs waiting in the sea for an easy turtle dinner, he said. Despite the great numbers of baby turtles that do not survive to reach adult stage, Peart said nature has compensated for it. "The reproduction cycle of the sea turtle is done on a statistical basis. The female turtle will lay 10,000 eggs and maybe only 100 will survive." Because of the threats to the baby turtles, Peart said turtle conservationists have encouraged residents to take a personal hand in the small creatures fight for survival. "Most people believe that state law prohibits them from touching the tiny sea turtles. That is not so...only the eggs cannot be handled. I would encourage anyone who sees the baby sea turtles wandering around on the beach to take them down to the water. It would eliminate the problems of artificial lighting on the beach." Peart said he handles three to four nests a day, but on some days he has moved up to seven. About one hour is taken to move each nest. Although he says poaching of the turtles and eggs has not been prevalent in delray Beach in recent years, he is still troubled by it." "Two weeks ago, someone caught a loggerhead turtle while she was laying eggs and hauled her off in a truck," he said. "Shortly before that, another turtle was taken in the sam fashion. These people don't know what they would get for stealing a whole turtle." Peart said he reported the turtle thefts to city police. |

|

John Peart Gives Baby Turtles A Fighting Chance By PETE GORDON Sun-Sentinel Writer DELRAY BEACH—John Peart's job is different, to say the least—he's been hired by the city to be midwife to Delray's endangered sea turtle population. During the past 30 days, Peart has taken care of about 3,500 unhatched turtles. The turtle eggs are being moved from the city's public beach to prevent them from being buried under 500,000 cubic yards of sand when the beach replenishment program starts within the next few months. Another 4,000 to 6,000 eggs will be moved before the sand pumping program begins. Most of the nets are being transferred to quiet, not readily accessible, privately owned beaches at Highland Beach where the 50- to 60-day incubation period can be completed relatively free of danger. As a midwife to the turtles, Peart's activities must be precise. He patrols the beach during the early morning hours to locate the newly made turtle nests in the sand. The eggs must be moved to the new location no later than 48 hours after they are laid—preferably within 24 hours—and the environmental conditions must be duplicated. Each nest contains from 110 to 160 eggs, but occasionally one will hold as few as 75 eggs. "I don't know why the long or short count, but I'm also puzzled that every nest is 18 inches below the surface, to the inch," Pearce said. He handles three to four nests a day, but on some days he has moved up to seven nests. Peart says it takes about an hour to move each nest. He's paid $5 an hour by the city. Turtle eggs, while protected by law from being taken by man, must still be protected from poachers. If the unborn turtle escapes this hazard, the next danger is its dash for the sea after it hatches. By instinct, the newly hatched turtle, about an inch or two in length compared to the mother's four-foot length, heads into the sea at daybreak. Still tender and soft-shelled, those that make it past predators—raccoons, gulls, crabs, and man—have to swim for their lives to avoid giant fish once in the sea. "I rescued one baby turtle the other day just as a crab was pulling it by the nose into his burrow," Peart said. "I snatched him from the crab's pincers and threw him into the sea." Conservationists have proposed newly hatched turtles be transported to turtle kraals at Hutchinson Island. Then, when about 1 year old, with a stiff shell and six inches or more in length, they will have a fighting chance when released into the ocean. Only about 4 to 5 per cent of the newly hatched turtles reach maturity if allowed to follow their instincts and dash into the sea. About 95 per cent of those released when a year old make it to maturity. |

©2023 Universal Beach Services Corp.